| Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, ca. 1914, gelatin silver print Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson AZ |

On March fourth of this year, Photography News wrote this about Margrethe Mather on the 125th anniversary of her birth in Los Angeles. " . . . . Margrethe Mather was a photographer who --through her exploration of light and form-- helped to transform photography into a modern art."

Despite her marvelous body of work, Margrethe Mather remains an enigmatic figure, best known for her association with Edward Weston . . . . However, many consider Mather to have been Weston's mentor and teacher. She shared with him her intuitive eye for composition and her innate sense of artistic style, "teaching him how to edit an image to its very essence."  |

| Imogen Cunningham Margrethe Mather and Edward Weston ca. 1922 Gelatin Silver Print 8 x 10 inches |

Collaboratively, Mather and Weston founded the Camera Pictorialists of Los Angeles in 1914 that became one of the most important camera clubs and exhibition venues in the country.

|

| Margrethe Mather Lady in White ca. 1917 Platinum print, 9 5/16 in. x 7 3/8 in. Collection SFMOMA |

Mather's early work was in the Pictorialist style, beautifully photographed images, veiled in hazy, soft-focus effects, such as the above Lady in White, taken in 1917. Mather and Weston had begun to employ the distortion of shadows to intensify the drama of their images. In her 1918 photograph of a Chinese poet, Moon Kwan, Mather strategically placed the poet's figure and his shadow in broad spatial areas to produce spare, but arresting compositions, that were quite ahead of their time.

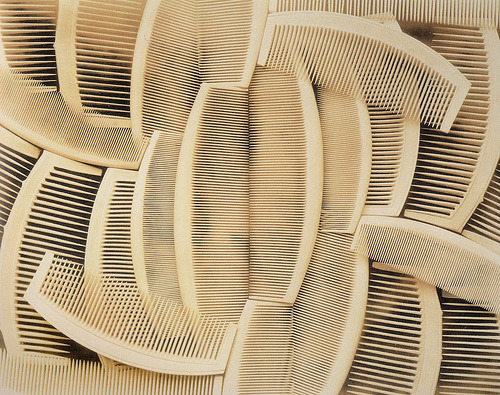

Margrethe Mather

Player on the Yit-Kim

ca. 1918

Margrethe Mather

Florence Deshon,(1894-1922) US motion picture actress.

ca. 1921

Margrethe Mather

Japanese Combs

ca. 1931

Mather, an artistic and political rebel and a liberated sexual woman, helped to turn Weston's work in a more experimental direction by introducing him to her circle of free-thinking artists, actors and theater people, and political activists. Although Weston appreciated by Mather's intellectual curiosity, and for a time was passionately in love with her, he was also frustrated with her lack of dependability and unpredictable nature. In 1921, Weston embarked on an affair with the Italian-born actress photographer, Tina Modotti. When they departed for Mexico in 1923, Weston entrusted his Glendale studio to Mather's care, however by 1925, she lost interest in sustaining the business and drifted back to her bohemian haunts on Bunker Hill in downtown Los Angeles. Mather continued to shoot photographs sporadically until the mid-1930s, when she appears to have turned her back on photography altogether.

Mather's photographs were more experimental than those being produced by her contemporaries. Margrethe Mather died on December 25, 1952.

Her work is featured in the book, Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration (W.W. Norton & Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2001).

In the early 1950s, recalling the greatest influences on his career, Edward Weston declared that Margrethe Mather was "the first important person in my life."

________________________________________________

Sources

http://giam.typepad.com/analog_photography_at_its/2011/09/margrethe-mather-1885-1952.html, retrieved December 17, 2013.

Grace Glueck, Art In Review, Edward Weston and Margrethe Mather, A Passionate Collaboration, April 4, 2003, http://www.nytimes.com/2003/04/04/arts/art-in-review-edward-weston-and-margrethe-mather-a-passionate-collaboration.html, Retrieved December 17, 2013.

SFMOMA, http://www.sfmoma.org/explore/collection/artwork/12772, Retrieved December 18, 2013

Margrethe Mather and Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration, http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/3aa/3aa602.htm, Retrieved December 18, 2013

![[Ruth Reeves]](http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/reevruth/reference/AAA_reevruth_11145.jpg)

,+Henrietta+Shore+n.jpg)