|

| Most 19th Century Chinese immigrants were single men. The Byrom-Daufel family of Tualatin retained this portrait, but descendants no longer have the Chinese family name. Photo courtesy of the Byrom-Daufel family. |

|

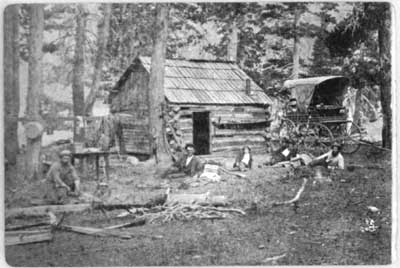

Japanese sugar plantation workers in Hawaii around 1890.

(Hawaii State Archives)

|

According to the 1900 U.S. Census, 24, 326 Japanese were living in America, primarily on the West Coast. Of that number, 393 were listed their residence in Wyoming. By 1910, the total population of Japanese in America had grown to 72,157, with nearly 2,000 living in Wyoming.[2] During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, white plantation owners imported large numbers of workers from Asia, primarily from China and Japan. The first labor recruits came from China in 1850. By 1887, 26,000 Chinese were working on Hawaii’s sugar cane plantations, however, approximately 38 percent of them eventually returned to China. Between 1868 and 1924, 200,000 Japanese workers came to Hawaii; eventually, about 55 percent of them returned to Japan. During this same period, 7,300 Korean workers came to Hawaii; 16 percent eventually returned home.[3] The pull to return to their home countries, especially with the severe conditions borne by the workers, disconnect from family, linguistic differences between groups thrown together on the plantation, and discrimination, remained powerful.

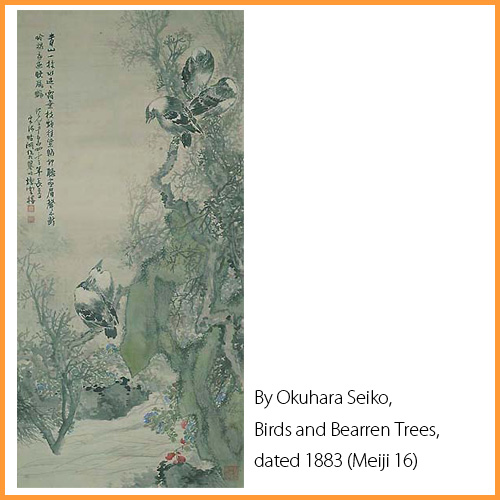

Asian female artists did exist in the East and in the United States. According to authors Deborah Cherry and Janice Helland in their book Local/Global: Women Artists in the Nineteenth Century, a group of forty-four Japanese women were selected to represent their nation, and exhibited their art at the Chicago World's Fair in 1983. Noguchi Shonin and Okuhara Seiko were part of a large, well established cultural group

in Tokyo with political, literary, and artistic achievements and, like many of their Western counterparts, taught aspiring young artists in their community, 'funded by the Empress and run by her daughter, Princess Yasu Mori.' [4]

In the West, women's artistic endeavors were increasingly in a studio-a "room of one's own" which became a necessary location in which to create. [5] For Asian women, their artistic practice and training often took place in an area of the family home. Families then, as now, varied by number, structure, relationships, region of origin, and dwelling. In addition, the family's attitude towards art and the practice of art by women had a significant effect on whether the woman would, or could proceed. Artistic families made demands that affected an artist's choice of genre or restricted access to her workspace and materials. The family could prove to be both beneficial and detrimental. What a woman artist made, or what she aspired to make, was closely connected to the spaces she inhabited and to her social relationships.

|

| Okuhara Seiko 1837-1913 |

|

| Okuhara Seiko Geese and Autumn Grasses ca. 1880 |

Her artwork and her independent lifestyle paved the way for vanguard women artists for generations to come, and the inscription on this painting bears witness to the strength of her convictions: “I, Seiko, have indeed arrived at the state in which I could control my brush at my will and scatter ink at my wish. I established my own style no longer emulating the old masters.” [7]

|

|

| Okuhara Seiko Crow on a Willow Branch with Orange Sky c.a. 1930s 11 1/4 x 11 inches |

1. Asia Pacific. Chang Phil, Asians in America Timeline. http://www.timetoast.com/timelines/3237. (Accessed January 21, 2013).

2. Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, Coming to America. The Issei: Early Japanese Migration. http://heartmountain.org/Immigrants.html. (Accessed January 23, 2013).

3. Encyclopedia of Immigration, Hawaii. http://immigration-online.org/541-hawaii.html. Published December 22, 2011. (Accessed January 24, 2013).

4. Weimann, 1981. 274.

5. Woolf, 1929.

6. Art Fact, Okuhara Seiko (1837-1913). http://www.artfact.com/artist/seiko-okuhara-89ztdsfx2e. (Accessed January, 25, 2013).

7. Okuhara Seiko Biography. http://artgallery.yale.edu/pages/collection/popups/newacquisitions/details05.html. (Accessed January, 25, 2013).

8. Art Fact. (Acessed January 25, 2013).