|

| Eliza W. Withington Studio Portrait with Rabbit Ambrotype, circa 1850s |

The camera, a technological device of incredible consequence for the modern experience was created shortly before mid-nineteenth-century. The medium, itself a product of science with its relative ease of process, was an enormously useful tool for recording the century’s discoveries seemed a dream come true for both scientists and artists. Artists had struggled for centuries to capture accurate images of their subjects, and photography provided the ability to capture the exact representation of the sitter-if not the soul. Photography challenged the place of traditional modes of pictorial representation originating in the Renaissance.

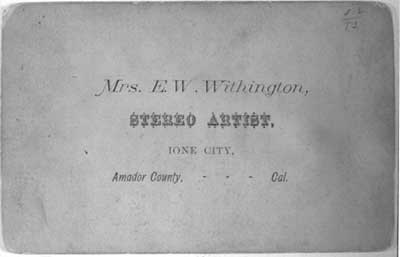

Early artists such as Elizabeth Withington (active 1857-1876) and Julia A. Rudolph (active 1852-1890) saw it as a mechanism capable of delving into the character of those they photographed, representing the optical truth of their chosen subjects.[3] Photography was also perfectly suited to an era which saw artistic patronage shift away from the elite few, toward a growing and increasingly powerful middle class that embraced both the images of the new medium and its affordable cost. By the late nineteenth century, photography had begun to become a recognized art form and was perceived as a vocation particularly suited to the “intuitive” female spirit, a profession in which women could excel, as they had in painting, printmaking, pottery, and woodcarving. [4]

|

| Mrs. Julia Shannon "Midwife and Daguerreian" Advertisement, 1850 |

In the midst of the influx of newcomers to the city, Shannon, made her appearance advertising in the January, 1850 issue of San Francisco Alta:

"Notice -- Daguerreotypes taken by a Lady. -- Those wishing to have a good likeness are informed that they can have them taken in a very superior manner, and by a real live lady too, in Clay street, opposite the St. Francis Hotel, at a very moderate charge. Give her a call, gents."[6]

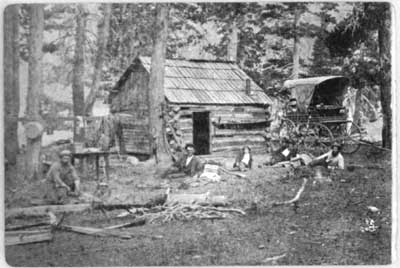

The first early female photographer I'd like to discuss is Eliza W. Withington. In 1852, Withington, accompanied by her younger daughter, traveled overland from St. Joseph, Missouri, to join her husband, George (1821-1900), who was operating a ranch in Amador County, California. The challenges of the trip were chronicled in the journal of a fellow migrant, Mary Stewart Bailey (see Jeanne Hamilton Watson, To the Land of Gold and Wickedness: The 1848-59 Diary of Lorrena L. Hayes).[7] In order to learn the art of photography, Withington traveled to the East coast in 1857. During her time in New York City, she visited the Matthew Brady Gallery (one of the most innovative and celebrated photographers of the nineteenth century).

|

| Eliza W. Withington n.d. |

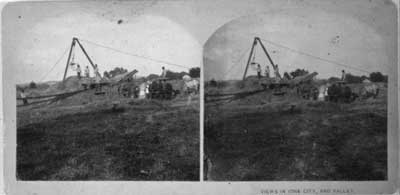

Withington's second daughter joined her in California later in 1857. After the death of her infant son in 1861, she seems to have stopped working for a time. It was not until 1871, after her daughters left home and she separated from her husband, that Withington's work reappears in print. As she resumed her career, Withington escaped the summer heat by touring small towns and mining sites in the mountains "by stage, private convey" or, when necessary, by hitching a ride on a passing "fruit wagon." Withington devised a uniquely assembled kit of travel-ready camera equipment, including supplies for developing her negatives in the field. Some of her home inventions included eight "dark, thick dress skirts" used as a makeshift developing tent and a "strong, black-linen cane-headed parasol" used to shade the lenses and as a walking stick for "climbing mountains and sliding into ravines." [9]

Eliza Withington was an intrepid and enthusiastic photographer. In addition to photography she was also a writer. In 1876, she wrote a fascinating article, "How a Woman Makes Landscape Photographs," that was published in the Philadelphia Photographer. Withington died of cancer in March 1877- she was just 51 years old.

|

| Eliza W. Withington 1873 |

1. Cornelia Butler and Alexandra Schwartz, eds., Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art. Essay: Sarah Hermanson Meister, Crossing the Line: Frances Benjamin Johnston and Gertrude Käsebier as Professionals and Artists. (New York: Department of Publications, Museum of Modern Art. 2010).

2. On the surge of female photographers, see Peter E. Palmquist, Camera Fields and Kodak Girls: 50 Selections by and about Women in Photography, 1840-1930 (New York: Abbeville Press, 1994).

5. Palmquist, Peter E. Women Artists of the American West. 100 Years of California Photography by Women, 1850-1950. http://www.cla.purdue.edu/waaw/Palmquist/Essay1.htm. (Accessed January 14, 2013).

6. Brown, Mary. Found SF, A Woman's View 19th Century San Francisco Women Photographers: Historical Essay. http://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=A_Woman%27s_View_19th_Century_San_Francisco_Women_Photographers. 1997. (Accessed January 14, 2013).

7. Palmquist, Peter. Clio: Visualizing History. Elizabeth W. Withington. http://www.cliohistory.org/exhibits/palmquist/withington/. (Accessed January 14, 2013).

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

_____________________________________________

Additional Reading

Palmquist, Peter E., and Gia Musso. Women Photographers: A Selection of Images from the Women ln Photography International Archive 1850-1997. Kneeland, California: Iaqua Press, 1997.

Palmquist, Peter E.. "Pioneer Women Photographers in Nineteenth-Century California," California History (Spring 1992), pp. 111-127+.

Palmquist, Peter E.. Shadowcatchers: A Directory of Women ln California Photography Before 1901. Arcata, California: Published by the author, 1990.

Palmquist, Peter E. (editor). Camera Fiends & Kodak Girls: Writings by and About Women Photographers 1840-1930. New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 1989.

Palmquist, Peter E. "Stereo Artist, Mrs. E. W. Withington; or, 'How I Use My Skirt for a Darktent,'" Stereo World, vol. 10, no. 5 (November/December 1983), pp. 20-21+.

Withington, Mrs. E. W. "How a Woman Makes Landscape Photographs," The Philadelphia Photographer, vol. 13, no. 156 (December 1876), pp. 357-360.

No comments:

Post a Comment